When it Comes to Work-Family Policy, U.S. Racism Stymies Common Sense Solutions

Advocates for family supportive policies in the U.S. have spent their entire careers fighting for reforms that most countries, especially wealthy peer nations, have had on the books for decades, some even a century or longer. Paid parental leave, publicly subsidized child care, extra cash incentives for families with dependent children, to name a few, all remain progressive dreams, while in other countries, politicians across the partisan spectrum would scarcely dare to threaten them. And the differences in outcomes, in relative happiness, between families in the U.S. and in countries with these policies in place are stark. International studies regularly show how much less stable and how much more stressed U.S. families are than their peers.

Researcher Jennifer Glass told Time Magazine that her research shows both parents and non-parents in countries with these policies are happier. Why? "My hunch is that countries that do a good job of supporting parents who are employed by providing high quality childcare at a reasonable price in that zero through five period end up with kids who are better socialized," said Glass. "They are better workers. They have fewer problems with delinquency and crime later on. They have a population with higher educational credentials. Those are externalities that affect everybody whether a parent or not."

So just what is it about the U.S. that has put families in such a uniquely hard position, despite the well documented benefits of better policies? While there are various theories—from American’s Protestant work ethic, to our rugged individualism, to our unique devotion to capitalism, contemporary data and historical evidence point to our country’s racism, particularly toward African Americans, as a key barrier to progress. Until the family policy movement considers racism as central to the problem and confronts these biases directly, workers and families will continue to be stuck in a system that works for no one.

When the long-standing program Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) was dismantled by a bipartisan coalition in the early 90s, it was met with little protest and widespread approval. The move to “end welfare as we know it,” as President Bill Clinton termed it, was seen as a long-needed end to policy run amok, and a blow against the racist stereotype of the “welfare queen.”

Such political backlash might have seemed bizarre to the political leaders and activists who fought for and won what was originally called Aid to Dependent Children in 1935. Those activists' intentions were two-fold. First, that the policy should help single mothers, and second that it should help them specifically avoid working outside the home while caring for young children. This pro-motherhood argument brought the U.S.’s earliest welfare policies into existence and mirrored those in other countries.

Historian Premilla Nadasen details the shift of pro-motherhood policies emphasizing time at home with children from being popular and moral to being seen as excessive and abused. Aid to Dependent Children was originally championed to support widowed white mothers to maintain their traditional roles as homemakers.

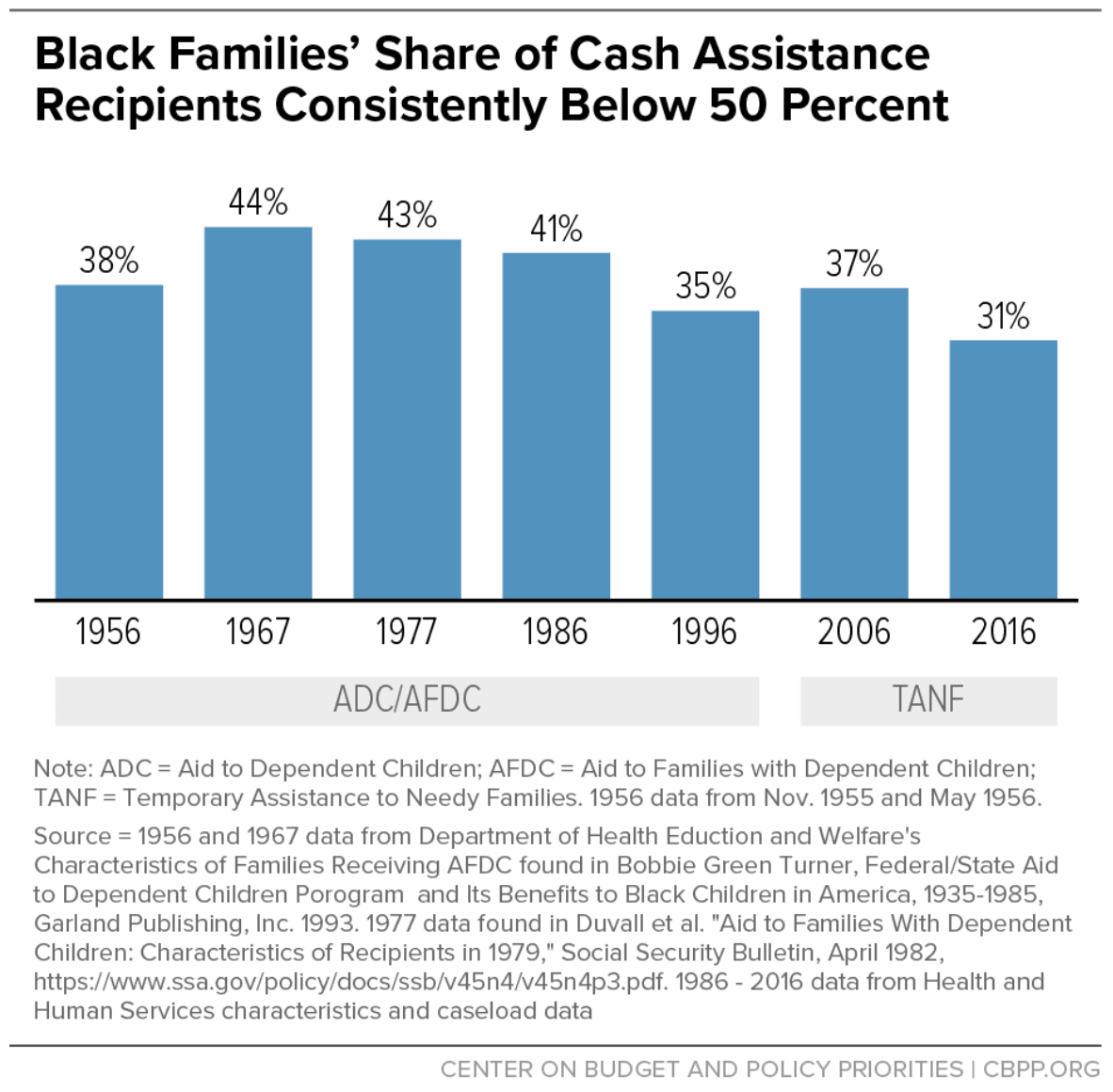

From inception it systematically discriminated against households of color, deeming them immoral and undeserving. The benefits were administered locally, and included subjective rules — like that the recipients be in a “suitable home”— that directly targeted families of color for exclusion. Local enforcers could make unannounced visits to homes and make biased judgments about whether the home was “suitable.” A comprehensive report from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities cites a field supervisor justifying the exclusions, stating that “Black families ‘have always gotten along’ and if made eligible for assistance, ‘all they’ll do is have more children.’”

Once increasing numbers of African American women began to qualify for aid when it was federalized after World War II, the policy fell under intense public scrutiny. At that point, Nadasen notes, “politicians and the press hammered away at the apparent overrepresentation of black women on the welfare rolls. However, taking into account poverty and out-of-wedlock birth rates, black women were actually underrepresented on ADC. Increasingly, the politics of welfare converged on the stereotypical image of a black unmarried, unworthy welfare mother.” The public panic over Black women’s reproductive decisions also stoked eugenics campaigns geared at restricting their child bearing. Mississippi State Representative David H. Glass called for forced sterilizations of Black women, arguing, “The Negro woman, because of child welfare, [is] making it a business in some cases of giving birth to illegitimate children.” The social tide shifted against this policy, even as it still largely supported white mothers.

Just as the Civil Rights movement and the fight against segregation and other Jim Crow policies gave Black women greater access to existing welfare provisions, a public backlash prompted the retrenchment of these policies. This primed the public to understand social support policies through a deeply racialized lens. As Nadasen writes in her book Welfare Warriors, “There was now a racially defined gender script that said good white mothers should stay at home, and good black mothers must go to work.” Thus, despite Black women’s demonstrated higher engagement in paid work, the myth of the Black mother with too many children, no intention of honest work, and a stockpile of luxury items paid for by honest taxpayers espoused during Ronald Reagan’s campaign for president in the 1970s had a significant impact on the electorate. Specifically, it cautioned the white voter against programs to help all families in need, due to the risk that it could be abused by the wrong ones.

While campaigning for president in 1976, then-candidate Ronald Reagan attacked welfare, and frequently invoked “that woman from Chicago,” a reference to the extreme case of Linda Taylor who swindled numerous people and government programs and was eventually sentenced to three to seven years in federal prison. Author Josh Levin writes “Taylor’s mere existence gave credence to a slew of pernicious stereotypes about poor people and black women.”

Photo Credit: UMass Amherst

In 2020, nearly thirty years after the welfare reforms of the 90s, the U.S. was closer to passing these long-needed policies than ever before. In the midst of the instability and unprecedented worry of many families driven by the pandemic, the Biden administration and its allies proposed a host of reforms as part of its Build Back Better budget reconciliation package, including investment in home and family care, child care and early education, and a permanent paid family and medical leave program that would allow workers paid time off to care for themselves or loved ones. Ultimately, the entire Republican establishment and a few key Democrats rejected the reforms and the legislation moved forward with the family supports removed, in favor of a climate, health, and tax centered bill.

How is it possible that in the nearly hundred years since the AFDC was created, Americans and political leaders remain reluctant to support policies with long-established track records boosting family well-being and national economic performance?

Criminology professor Kevin Drakulich theorized that implicit bias is driving some of the resistance to these policies.

In a study designed to understand the shift away from social assistance, Drakulich found powerful evidence that racism still impacts our social policy: “Among non-Hispanic whites, implicit racial bias is significantly associated with opposition to policies designed to ameliorate these inequalities as well as support for punitive crime policies.” In other words, the same attitudes that promote “law and order” policies with a demonstrated record of violence against Black people, also suppress public support for social supports that help ameliorate long-standing racial inequalities and intensify hardships for black and brown families.

Similarly, a 2018 study by researchers at Stanford found that since 2008 and the election of Barack Obama, white Americans have declined in their support for welfare programs due to what they term “racial resentment,” a feeling that the status of white Americans is in decline while that of African Americans and other people of color is rising. In fact, research shows that the majority of those who benefit from welfare programs are white, and that significant wealth disparities remain between white families and families of color. The Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis reports that “White Americans hold 84 percent of total U.S. wealth but make up only 60 percent of the population—while Black Americans hold 4 percent of the wealth and make up 13 percent of the population.”

The U.S. is one of the few countries on the planet that doesn’t provide paid leave for new mothers (though several states and the District of Columbia have attempted to solve this problem in recent years). Sociologist Joya Misra told the BBC that while European countries instituted national paid leave programs for new mothers as a way to boost reproduction after World War II, the U.S. was concerned with getting working white mothers back to the home, and with boosting reproduction among families it saw as desirable, while keeping it in check among Black mothers and immigrants. Black and immigrant mothers have always engaged in paid work in greater numbers than white mothers. Critically, even as the U.S. implemented worker protections in the 20th century, it specifically excluded from protection the occupations that people of color were most heavily represented in, including domestic and agricultural work.

While country after country around the world created a tax-payer social insurance system akin to Social Security to ensure first mothers, and later fathers, could take time off after the birth of a new child without facing financial penalty or losing their jobs, the U.S. resisted such universal changes. Why should tax payers pay for families who couldn’t afford parenthood to become parents? Paid parental leave, like health insurance, became a perk from one’s employer, giving the best compensated workers yet more support, while workers in the lowest-paid professions, where people of color are heavily overrepresented, were left behind. Having federally administered, taxpayer supported universal benefits remains something Americans are uniquely skeptical of today. A Pew Research Center study showed that while 82 percent of Americans support paid leave for new mothers (and 69% for fathers), more than 70 percent of both Republicans and Democrats said the pay should come directly from an employer, not the state or federal government. In practice, this means only the most privileged workers have access to paid leave.

Today, African American women have significantly less access to maternity leave than white women. This creates huge negative impacts on their health, their birth outcomes, and the health and wellbeing of their children. We know, from decades of research, that access to paid family leave and high-quality early childhood education and care brings a host of benefits to mothers, children and the economy alike. Yet as my colleague at New America Vicki Shabo notes, today “just 24 percent of private-sector workers have paid family leave at their jobs through employer-provided benefits.”

Thus, across decades and dozens of policies, the same pattern shows up: the racist logic of opposing family policy to limit minority mothers’ access creates massive racial inequalities, and hurts the population as a whole.

Today, progressives are fighting for a robust, year-round child tax credit, which was available to working families for one year during the pandemic. The plan, which has since expired, garnered support from Americans on both sides of the aisle. The prohibitive costs of childcare and the residual stress from the pandemic means families with children throughout the country are suffering emotionally, physically and economically, even those with two working adults in the household. Yet once again, the specter of that kind of parent, the racist myth of someone who will take advantage of the program and not work, has reared its head. Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV) has vowed not to support a CTC that doesn’t come with a minimum work requirement, and Democrats as a whole seemed inclined to cave to this request. But, when given the opportunity to put the expanded CTC with a work requirement into the omnibus spending bill Congress passed at the end of 2022, Democrats passed.

As a consequence, the U.S. ended up without an expanded and popular family policy despite data showing in the months the expanded CTC was in effect, nearly three million children rose above the poverty line. One study by a coalition of progressive groups found that Americans are more likely to support an expanded CTC if it is framed as assistance to working families, rather than as a way of alleviating poverty, despite the fact that it had an incredible and historic impact on poverty. So far Democrats seem content to leave the CTC in the past, despite its popularity among voters, especially those who benefited directly or knew someone who did.

Analysis by the U.S. Census Bureau shows the impact of the temporarily expanded CTC on child poverty, across race.

For too long racist biases have stopped progress in its tracks, leaving Americans lagging far behind their international peers and too susceptible to crises like recessions and pandemics and inflation. This means advocates and activists in the movement for work-family justice and family-supportive policies must join the anti-racism effort whenever and however possible, and publicly proclaim that the fight against racism is critical to our movement and ultimately the security and happiness of families across the country. Women of color leaders in the movement have been making this case for decades, and the brave leaders of the welfare rights movement from the Civil Rights movement through the 90s gave us the templates for making anti-racism an explicit part of the movement for family reforms.

In Welfare Warriors, Premilla Nadasen writes that the 30,000 to 100,000 largely women of color who made up the 1960s welfare rights movement “should be defined as part of the women’s movement of the 1960s,” and that “[T]heir version of women’s liberation included the right to stay home and raise children as well as seek employment outside the home.”

Supporting parents, especially parents of color, upon the transition into parenthood is a critical policy point to start closing these gaps. What is more, policies to support working families - parental leaves and high-quality childcare - have broader economic benefits and long-term positive childhood outcomes as well. Thus, supporting working parents, especially parents of color, is a way to support all of us as well.

Yet, we continue to shy away from clear evidence that family policy is critical to racial justice, often because polling shows this may be off-putting to some voters—in truth, those voters’ fears have held us back for decades. Instead, we should take the biases that lie behind those fears head on, to show them to be false, to call them out for the prejudices they are, and to emphasize the real and ongoing damage they’re causing families of color. That the lack of effective family policy is also detrimental to white Americans is undeniable. But, until we confront the racist fears and resentments, history shows us, self-interest alone is not enough to overcome racist bias.

A family policy movement without anti-racism is a movement destined to fail. And too many families can no longer afford failure.